The Misinformation I Fell For

I fell for these four claims. You probably did too. Misinformation doesn't just happen to "other people."

I consider myself reasonably informed.

And yet, I’ve believed things that weren’t true. Not from sketchy blogs or conspiracy theories. From Scientific American. NPR. The New York Times.

Here are four examples that changed how I think about misinformation.

The maternal mortality crisis

For years, I read that maternal mortality rates were skyrocketing in the US. Scientific American, NPR1, PBS, and Mother Jones reported deaths had more than doubled in the last 20 years.

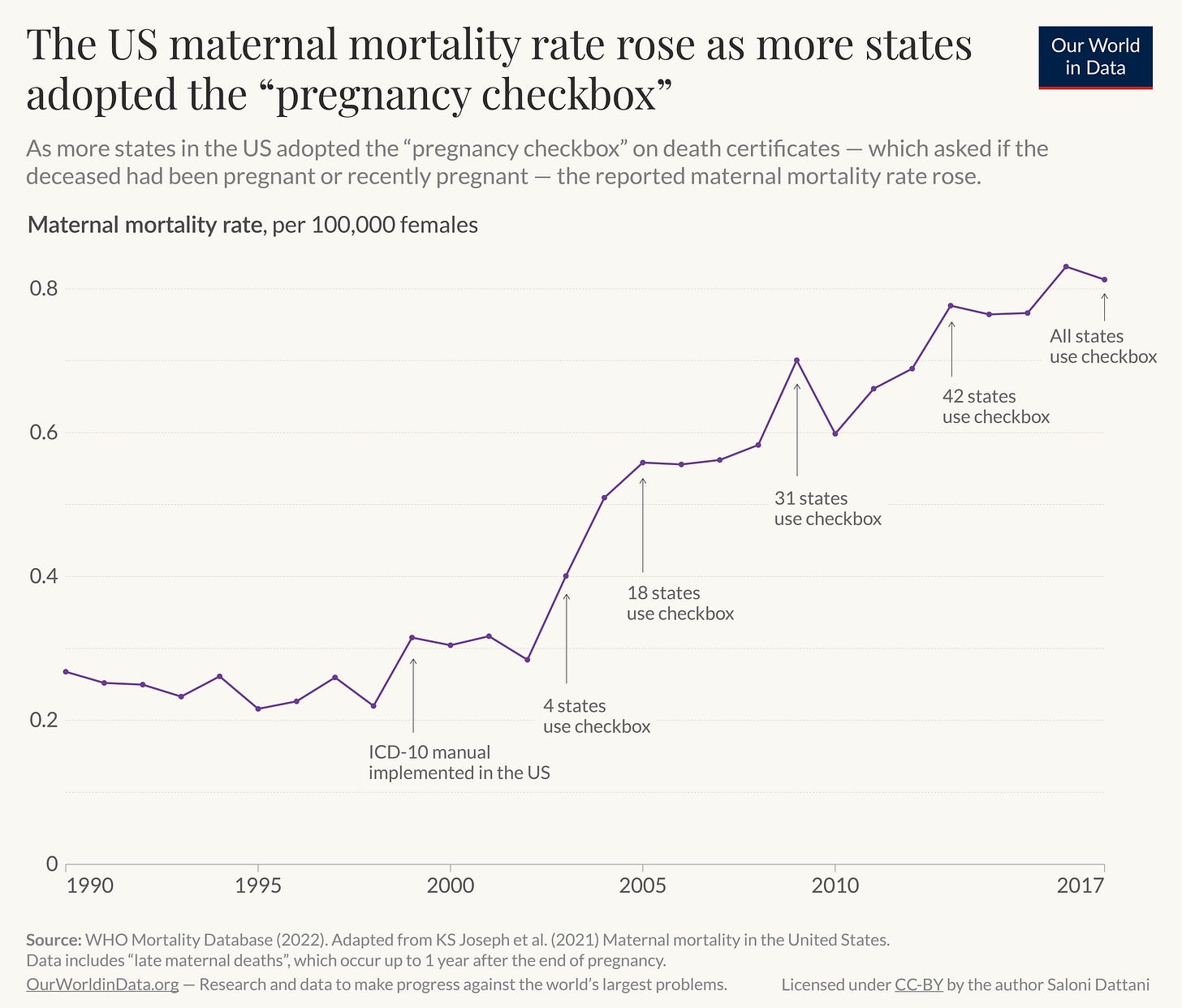

But researchers found the rise was largely from a change in measurement. Between 2003 and 2017, states gradually adopted a new checkbox on death certificates to flag pregnancy-related deaths.

The checkbox was meant to catch deaths that had been missed.

It did. But it also swept in deaths that weren’t pregnancy-related. People who died in car accidents. People who died of cancer. If the checkbox was ticked, they at times went into the maternal mortality rate.

A quality assurance study across four states also found that 21% of death certificates with the checkbox ticked were false positives, people who weren’t pregnant.

For reasons like this, when a state flipped the checkbox on, maternal mortality doubled immediately. The year of implementation.

Because states adopted the checkbox on different years, the national average appeared to rise smoothly.

The checkbox caused most of the statistical rise. Not an actual doubling in deaths.

Some news outlets corrected the claim. Some sources, like the interim CEO of American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, pushed back against clarifying the overestimation because it might undermine advocacy and community efforts.

The paycheck-to-paycheck statistic

You’ve probably heard that 60% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck. It fueled my thinking about the state of America.

But that original statistic doesn’t distinguish between someone struggling to afford groceries and someone making $150,000 that invests aggressively and keeps minimal cash on hand. That same LendingClub survey found that 40% of people making over $100,000 live “paycheck to paycheck.”

When people hear “paycheck to paycheck,” they think hardship. That statistic measures something different.

The data center drought

The New York Times ran a piece about a data center in Mexico causing regional water shortages. The article featured photos of residents suffering from lack of water.

Some important details weren’t included:

At maximum permitted usage, the data center uses one-quarter the water of a single car factory. About 0.1% of regional water. (Maximum permits are usually way higher than actual use. This is already an overestimation.)

Looking at the bigger picture, a new facility added 1/1000th to regional water demand. This is unlikely what turned day-long droughts into week-long droughts.

The facts were accurate. The framing created a false impression.

(Thanks to Andy Masley)

The 82-cent wage gap

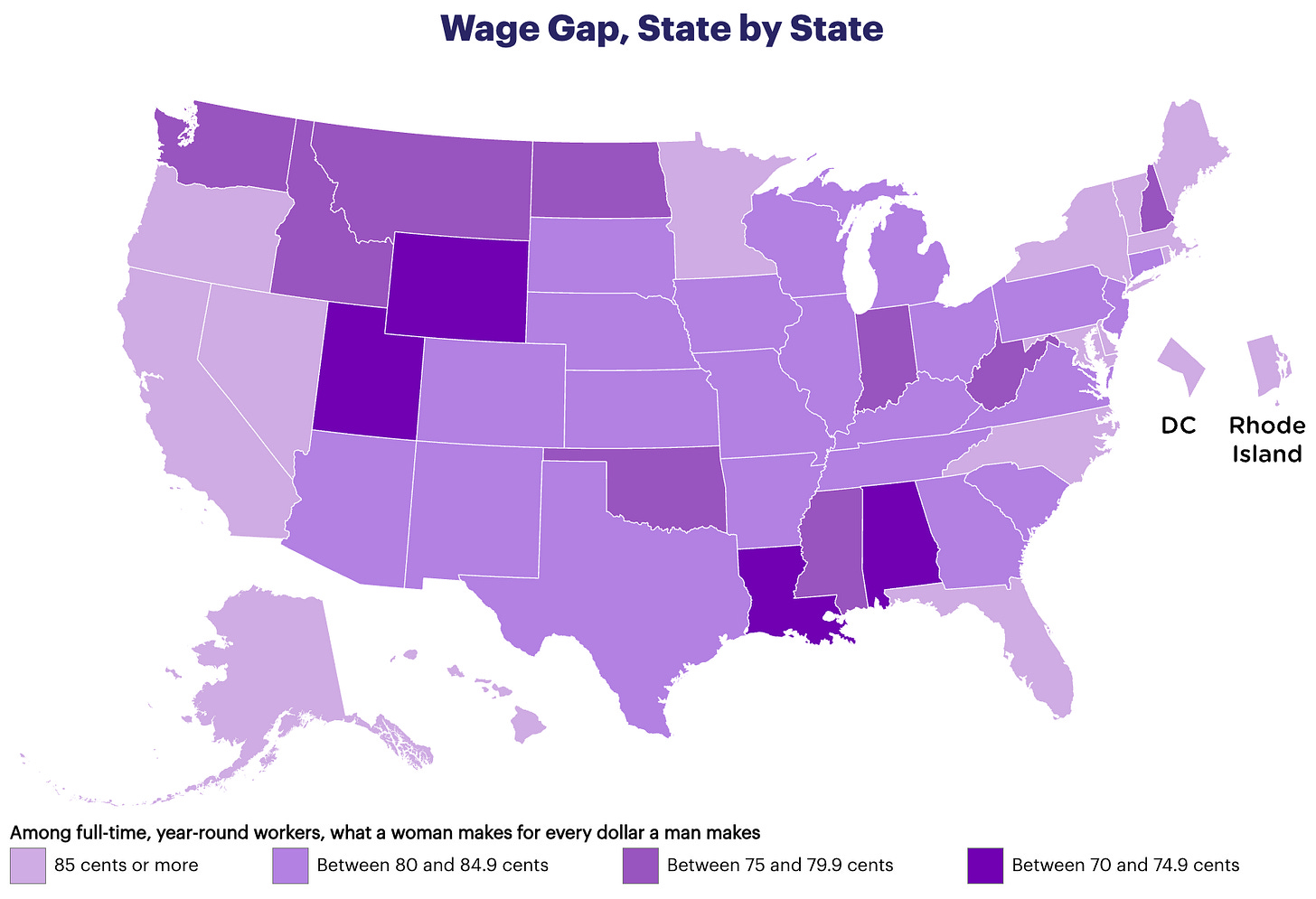

Women earn 82 cents for every dollar men earn. This figure drove advocacy in my circles for years and convinced me the labor market was rigging the game against women.

Then I learned what the number actually measures.

The 82-cent figure compares all working women to all working men, regardless of their jobs. It stacks a female teacher against a male software engineer. Men dominate higher-paying fields like tech and finance. Women cluster in lower-paying occupations like education and social work.

Pew Research found that education, occupation, and work experience explain much of the gap.

The National Women’s Law Center publishes the 82-cent figure prominently. Their main wage gap page doesn’t mention these factors. Their guide “How to Win an Argument about the Gender Wage Gap” lists discrimination first, then acknowledges “no one is claiming discrimination explains the entire gap.” But when you lead with discrimination and bury context, you shape what people believe.

A wage gap exists. Women face real barriers entering high-paying fields. But the 82-cent figure doesn’t measure the discrimination most people imagine when they hear it.

What these have in common

None of these are outright lies. But the framing creates misleading impressions that shape how millions see the world.

If you believe maternal mortality is skyrocketing, America looks like it’s failing mothers. If you think 60% of Americans can’t pay bills, the economy looks broken. And you wonder why others don’t share your urgency.

Meanwhile, those others see exaggerated claims and misleading statistics. They’re not ignoring a crisis. They’re seeing a different reality.

I didn’t catch these distortions until I read outside my usual sources.

This is how institutions lose trust. This is what successful misinformation looks like: it comes from sources we trust, created by people genuinely trying to inform, who believe the urgency justifies the framing.

Successful misinformation isn’t deepfakes and AI-generated fake news sites. Brookings finds that only one percent of social media users ever see that content, usually those who seek it out.

The misinformation that actually shapes our world comes from the institutions we’ve love and trust, institutions that I still love and trust, motivated by the best intentions.

Thanks to John Quiggin for flagging that NPR posted an article correcting the maternal mortality claim. Ideally, NPR would have corrected the claim in the original article (which still states maternal mortality doubled without a clear caveat). The correcting article’s title “How bad is maternal mortality in the U.S.? A new study says it’s been overestimated” almost makes the finding sound like a one-off study. To NPR’s credit, the article’s text does do a better job of showing that this was a big deal affecting the CDC counting itself. Scientific American seems to have put out a separate corrective article, though it’s paywalled.

This is a great piece thank you for writing it

Haha I fell for these too! I was living paycheck to paycheck while making $40/hr in California at AMD. Had a blast spending all the money I made at my internship, but I also felt like it was slightly dishonest to compare me to someone who can't afford food most nights. This experience radicalized me against Bernie